Workers planting bamboo in a slope needing rehabilitation at the Didipio mine. Photo Courtesy of OceanaGold - Abe Almirol

The strategic plan to develop Bamboo has been in the portfolio of the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) many years back. As a chief raw material source for the flourishing Philippine handicraft industry, the demand for Bamboo increased further over the years because of its emerging uses in construction, agriculture, and fisheries.

Bamboo development was mentioned in several Physical Framework Plans that the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) mandated Local Government Units (LGUs) to prepare. At the national level, the most comprehensive among these plans is the Philippine Bamboo Industry Development Roadmap (PBIDR) crafted by the Board of Investments in 2016.

The PBIDR has called Bamboo as the ideal renewable resource that can thrive easily. If managed well, it could provide sustainable raw materials for myriad uses -- house and kitchen utensils, farm implements, furniture and handicrafts, house décor, raw material for construction, banana props, fish pens, banca outriggers, and fuel in the form of charcoal and charcoal briquettes.

Bamboo also emerged as the source of pulp and paper, textiles and clothing, and renewable energy resource in the form of chips and pellets. Lately, beer and energy drinks have also been manufactured from Bamboo.

In an article published by the Philippine News Agency in 2018, DTI Secretary Ramon Lopez said he will work closely with DENR Secretary Roy Cimatu to “work out a sustainable mining development plan through planting Bamboos for rehabilitation.”

Bamboo in Didipio mine’s FMRDP

The PRJ interviewed the environment manager of OceanaGold’s Didipio mine operations, Engr. Jason Magdaong, to inquire how the company considered Bamboo in their Final Mine Rehabilitation and Decommissioning Plan (FMRDP). He confirmed the extensive use of Bamboo in their mine rehabilitation and reforestation efforts. The FMRDP is the blueprint of how the mine would become after decommissioning. It is a requirement for operating mines mandated by Republic Act 7942, otherwise known as the 1995 Mining Act.

“We’ve considered Bamboo as a rehabilitation and plantation species because it fits well our mine. It is fast growing. Also, it has a very good performance in soil erosion control, and works best in rehabilitating disturbed slopes and riverbanks,” Magdaong explained.

Bamboo also has strong carbon absorption capacity and good properties in absorbing heavy metals in normal conditions, that is why generally recommended for most mines, although Didipio does not have pressing concerns on these aspects.

Magdaong said that their Didipio nursery has started producing Bamboo propagules two years ago in response to DENR’s call to support the development roadmap. Bamboo has been planted in Didipio’s waste rock dumps which are already topped with soil.

“The performance of Bamboo as a rehabilitation species is generally good,” Magdaong affirmed.

Initially, OceanaGold used the kawayang tinik (Bambusa blomeana) and bayog (Bambusa merrilliana) which are locally abundant around the Didipio mine site.

“When we heard of the giant Bamboo, we thought of using it because of the promising livelihood opportunities it can offer,” Magdaong added.

The giant Bamboo (Dendrocalamus asper) has thicker flesh and grows taller than local species like the kawayang tinik, bulo (Gigantochloa levis), buho (Schizostachyum lumampao), and bayog (Bambusa merrilliana).

The giant Bamboo is preferred by manufacturers of engineered Bamboo (such as floor tiles, boards, and blocks) because of its superior properties.

Magdaong believes that leaving behind a Bamboo Forest along rehabilitated areas and targeted reforestation sites elsewhere could create a flourishing industry for Didipio folks.

“The power lines that would be left behind after the mine closes are already three-phase configured, just the kind of electrical power connection needed in establishing industries,” Magdaong explained.

Bamboo offers a two-pronged solution according to Magdaong: it mitigates environmental impacts, and at the same time, it offers a supply of resources for a budding industry that would address the social and economic displacement of workers and local folks affected by the eventual mine closure.

“Our strong adherence to regulatory requirements and consistent advance towards achieving our goals … allow us the opportunity to nurture the value of our skills, our safety, and our responsibility for the environment, and for the communities to which we belong,” OceanaGold (Philippines) President, Atty. Joan D. Adaci-Cattiling said.

As the Didipio FTAA contractor, OceanaGold (Philippines) has committed beyond adherence to responsible mining principles in achieving its goals, do more for Didipio for it is the community that they belong to.

Bamboo and Environmental Remediation

There is an established claim that Bamboo can produce more oxygen and absorb more carbon dioxide than trees. This makes it perfect for restoring disturbed ecosystems and for remediation of greenhouse gas emission. Because of this, Bamboo is also widely used in urban forestry and landscaping.

The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 did not identify Bamboo as an invasive species. There are currently no restrictions on planting it. In fact, the Ecosystems Research and Development Bureau of the DENR has been producing Bamboo planting materials for the National Greening Program several years back.

Thick Bamboo clumps provide excellent shelter for wildlife. Monitor lizards, locally known as bayawak, are frequently seen along dense clusters of Bamboo by folks gathering young shoots or labong, a local delicacy. The deep roots of Bamboo usually form spacious crevices that are ideal shelter of many species of reptiles and amphibians. Small birds are also found to nest in the thorny branches of Bamboo culms.

“We are also planting other species alongside Bamboo to create a condition for a restored biodiversity. Bamboo is compatible with other species, and one thing good is it blends well with all other species we are planting,” Magdaong explained.

Economic Potentials of Bamboo

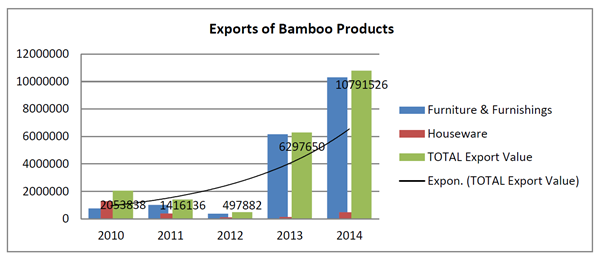

The PBIDR cited that Bamboo products exported increased significantly from 2010 to 2014, growing from US$2,053,838 to US$10,791,526 annually. The roadmap also estimated the demand for Bamboo culms by current industries and sub-sectors would amount to 21,250,874 culms annually. If pulp and paper production and Bamboo chips for fuel would attract more investments, the total demand could climb up to 107,058,770 culms per year.

The PIBR also recognized Bamboo as a US$11.21 billion industry worldwide as of 2009. In 2015, China has been the top exporter of Bamboo products valued at US$1.398 billion and the Philippines was ranked 5th worldwide with exports valued at US$54 million, according to the International Bamboo and Rattan Organization.

Stakeholders in the Bamboo industry involve Bamboo clump/plantation owners, gatherers, traders, sawali and basket weavers, and furniture and handicraft producers. They own or work in small, unregistered shops, thus, considered as part of the informal sectors.

Sources from the furniture industry estimated around 190,000 or 10% of the total workers in the furniture and handicraft sectors work in Bamboo-related handicraft. Pangasinan, particularly in the towns of San Carlos, Binmaley and Urbiztondo, is the country’s Bamboocraft centre. But since Bamboo is found all throughout the country, bamboocraft-making are also be found in all the provinces.

As Bamboo gained the spotlight in the rehabilitation of the Cagayan River, the inter-agency Task Force Build Back Better has laid up a complete plan beyond using the species for riverbank stabilization. They mobilized the Technical Education Skills and Development Authority (TESDA) to train laborers from local communities on seedling propagation and Bamboocraft. Paid by the Department of Labour and Employment (DOLE) under the Tupad Program, locals were mobilized to plant Bamboo in the riverbanks The move has set in motion a strategic Bamboo supply development in the region.

Opportunities and Challenges

The popularity of Bamboo could be seen in online markets, where varied products such as blinds, steamers, sticks, fence, sala sets, tumblers, mugs, pens, etc. are offered for sale. Giant Bamboo cuttings are also sold online by Bamboo nurseries at P58.50 a piece, excluding delivery cost.

The PBIDR has identified key production areas in Batangas (Euro Integrated Farms & Supply, Inc.), Pangasinan (CS First Green Agri-Industrial Development, Inc), Negros Oriental (Philippine Bamboo Foundation, Inc.), and Antipolo City (Carolina Bamboo Farm). These serve as primary sources of planting materials needed to produce enough supply of Bamboo culms in the country.

The production of toothpicks and barbeque sticks alone has gone a long way in the Bamboo industry. A small enterprise in Iloilo has grown over the years and now producing large volume of quality toothpicks and barbeque sticks using mechanized equipment.

However, as revealed in the PBIDR document, Chinese exports are much cheaper than locally produced Bamboo products. Processing machines are imported because there are no local fabricators yet. There is also a need to set the specifications for Bamboo construction materials so that it will be used in high-level construction sites. These are the ways forward for the Bamboo industry stakeholders to work on.