If businesses have anything to learn from the Covid-19 pandemic, it should be making their operations agile. Business agility means the ability to adjust swiftly to market changes both internally and externally, address customer demands quickly and flexibly, and adapt and lead continuously the improvement initiatives in a productive and cost-efficient manner, while maintaining the required level of quality (Agile Business Consortium 2021). It is also based on the principles of teamwork, autonomy, and alignment. Having an agile business is becoming a strategic imperative because companies these days face more demanding customers, tougher competition (Hammer 2002) and a disrupted, volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous, and diverse world. As Bansal and MacMillan (2021) posited, only a handful of events made it obvious that every business is embedded within a larger open system which necessitates for building agile, adaptive, and resilient organizations.

In order to achieve business agility, first, it has to become part of corporate objectives which can be translated into process-performance goals through balanced-scorecard and economic-value-added techniques. The process-performance goals can be attained by putting in place a robust, flexible, and fast-response business processes. A business process is defined as “a construct consisting of a set of clearly pre-defined, structured, and logically related activities that work together and use resources in order to transform specific inputs into desired outputs (Chountalas & Lagodimus 2012).”

When we talk of business process, we are reminded of the bigger umbrella of business process management which is a structured methodology to improve performance that focus on disciplined design and careful execution of a business’ end-to-end processes (Hammer 2002). It encompasses business process design, business process improvement, and business process reengineering.

Business Process Design is the first phase as the designer charts the business processes to be implemented. At this stage, parsimony of process steps is observed but provisions for shifting to ‘externalities scenario’ operations are included. Parsimony in this case means employing simple methods and using fewer resources. The activities in a process are aligned to serve customer needs. Furthermore, the design should specify the duration of doing the activities and the respective responsible persons. It should also be ensured that the defined performance objectives mentioned earlier are applied consistently across the processes to ensure repeatability and consistency (Hammer 2002).

The second phase is Business Process Improvement. In here, the process owner can make minor modifications to the process design in order to fix a flaw or address new issues. Among the tools used to improve a process is Six Sigma which uses statistical analytic tools to uncover flaws in process execution. The most widely used methodology is known as the DMAIC (define, measure, analyze, improve, and control). The premise here is that businesses have to be consistent in terms of high levels of quality, low levels of cost, and that a disciplined, organized approach will eradicate variance, waste, and error in the operations. However, Six Sigma cannot address business problems at a superficial, phenomenological level and as Hammer (2002) posited, it can only work effectively if placed under Process Management. Furthermore, due to its project-oriented and problem-solving focus, it cannot help in discovering better processes. The underlying assumption here is that the existing process design is sound and needs minor fine tuning to be efficient. As such, this kind of assumption will not lead to substantial performance improvement. If it happened to be that there is a wide discrepancy between the existing process performance and the desired performance, the process owner should initiate Business Process Reengineering (Hammer 2002). One should take note that the wide discrepancy in performance can be due to system disruption which we have witnessed during the pandemic.

On Business Process Reengineering, it is the third phase which is an intentional and comprehensive redesign of work. The difference between Business Process Improvement and Business Process Reengineering is analogous to the difference between waste and non-value-adding work. Waste is generated from the erroneous and inconsistent individual activities performed and it can be eliminated using DMAIC. On the other hand, non-value-adding work holds the process together hence cannot be eliminated at once. Business Process Reengineering aims to reduce the number of non-value adding work. While it is easy to identify non-value adding work, it is difficult to reorganize the process to have less of it (Hammer 2002).

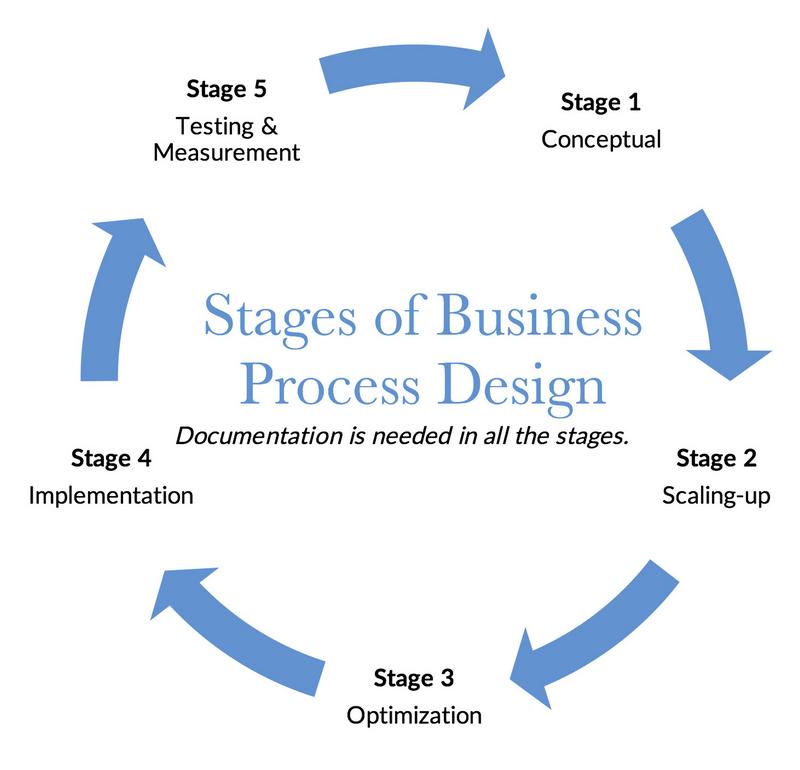

In all the three phases of Business Process Management, the stages of Business Process Design shown on Figure 1 are undertaken.

In Stage 1, the activities in a business process are conceptualized and arranged sequentially to come up with the desired output. This require a lot of thinking, i.e. idea generation and brainstorming. In Stage 2, the preliminary business process design is further analyzed and more details are added such as control mechanisms (e.g. stage gate, decision, etc.). In Stage 3, the process is optimized by determining the likely pain points, bottlenecks, or vulnerabilities and countermeasures are put in place. To ensure agility, the process undergo “What-If” Scenario Analysis where various scenarios are looked into to determine countermeasures in case such scenario would occur. The scenarios generated can be as many but those which will be considered for analysis are those with high likelihood of occurrence. Layers of protection are also put in place to ensure that the likelihood of process failing is low and that it is not disastrous. Moreover, potential unintended consequences are identified and to ensure productivity gains, the process is optimized first before automation (Davenport and Brain 2018). After the approval of the process design by the client, it is implemented (Stage 4). In here, the work area and equipment are rearranged according to the designed process and employees are trained on executing it. Control mechanisms are installed and the IT systems are reconfigured. Troubleshooting is also done at this stage. In Stage 5, the process is tested and the objectives in terms of Key Performance Indicators are measured to determine if the process delivers as intended. If externalities or emergencies occur and the testing and measurement results are the same as that during normal operations, then the process can be considered agile. In view of continuous improvement, the 5-stage cycle repeats.

The stages in the foregoing paragraph were adapted from the general steps in the process design of chemical plants and petroleum refineries and follow the plan-do-check-act framework of the International Organization for Standardization.

One should take note that in all these endeavors, the application of design thinking is imperative where a wider field of view is required and external stakeholders are consulted (Bansal and MacMillan 2021). It will also be helpful to chart the business’ ecosystem and imagine the potential disruptions which could come from its various parts. Failure to have this ecosystem view is one reason why the US supply chain broke down at the onset of pandemic recovery when the demand for imported goods soared.

As Hammer (2002) mentioned, business success results from the effective performance of a well-designed and agile business processes. By putting in place such kind of business processes, companies will be prepared for system upset and they can help stabilize the system and prevent future disruptions (Bansal and MacMillan 2021).

-----

References

- Agile Business Consortium. 2021. [online] Available at: https://www.agilebusiness.org/page/WhatisBusinessAgility [Accessed 9 October 2021].

- Bansal, T. and MacMillan, K., 2021. How Your Organization Can Prepare for Systems Disruptions. [online] California Management Review. Available at:

https://cmr.berkeley.edu/2021/03/how-your-organization-can-prepare-for-systems-disruptions/?fbclid=IwAR17ue8SBUCZ5YaLrFOWL_vkjf2MOG551WRLEp9QbNJsYH0Xk2gskTY028c [Accessed 15 October 2021].

- Chountalas, P and Lagodimos, A 2012, Volume of Essays in Honour of Prof. S. Karvounis, University of Piraeus, Piraeus.

- Davenport, T. and Brain, D., 2018. Before Automating Your Company’s Processes, Find Ways to Improve Them. [online] Harvard Business Review. Available at:

https://hbr.org/2018/06/before-automating-your-companys-processes-find-ways-to-improve-them [Accessed 24 October 2021].

- Hammer, M., 2002. Process Management and the Future of Six Sigma. [online] MIT Sloan Management Review. Available at:

https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/process-management-and-the-future-of-six-sigma/ [Accessed 9 October 2021].

-----

[Photo credit: Sikov, from Adobe Stock]

-----

Jed M. Bellen is the Chief Executive Officer and Founder of Bellen Management Consulting, O.P.C. based in Bacacay, Albay, Philippines. His specializations are on Business Process Management, Strategy, and Project Management. The clients he has helped to date are artist, educational institution, broadcast and print media, and a religious store. He is a Project Management Professional, a Stanford Certified Project Manager, an MBA from Asian Institute of Management (2011) and a licensed Chemical Engineer (BS Chemical Engineering, Bicol University, 2005). He can be reached via jed.bellen@bellenmc.com.