It has been almost four decades since I have worked in the resources and energy industry. My career history can be set against the backdrop of the ups and downs of the industry starting from the time I began working as a government petroleum geologist up to the present where I am both a government regulator and a private law practitioner.

I witnessed the paradigm shift in the industry when environmental protection became the norm in the 80s and indigenous peoples' rights were given legal recognition in the 90s. The millennium saw how green energy transition and digital transformation drove companies to adhere to the ESG framework extending sustainability beyond environmental issues to encompass climate change, human rights, monitored revenues, and strict adherence to laws.

I embarked on a geology course upon the persuasion of my parents who wanted me to have a stable and relatively high-paying job. A relative was gainfully employed as a structural geologist in a government corporation and my parents believed that the profession offered numerous opportunities for career advancement.

So, there I was, a wide-eyed high school graduate from a small parochial school, enrolled in UP in a freshman block composed of 15 geology and 15 engineering majors. The group was a merry mix-up of kids from both exclusive and public schools, and uber-smart guys from Xavier School and Philippine Science High School who ate advanced calculus for breakfast. Our block president became active in university politics and was elected as University Student Council Chair, a prelude to his eventual rise as senator of the republic. Many in our freshmen block pursued their PhDs in geology while surprisingly, a good number became lawyers like me.

Amidst the political turbulence and economic chaos brought about by the assassination of Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino, I obtained my geology degree. Little did I realize that graduation from the university was just the beginning of the real challenge. Employment in the geoscience field depended highly on the price of commodities, particularly metals and oil. We entered the job market when metal and oil prices in the eighties were depressed. Qualifying for a geoscience job in the resources industry was difficult. The options were either being employed as a contractual worker in government or staying in the university as a research assistant while pursuing graduate studies. Private companies were not hiring and in fact retrenching their technical people.

In the 1970s, copper prices trended upward and peaked. The country’s copper production continued and boomed until 1980 when output recorded its highest production. Meanwhile, the 1973 energy crisis, also known as the Oil Shock of 1973–74, was a period of skyrocketing energy prices and fuel shortages resulting from an embargo by Arab oil-producing nations in response to U.S. support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War. These periods saw the initial boom and increase in demand for geologists.

However, in 1986, Saudi Arabia grew tired of attempts to stabilize the oil glut in the market by curbing its output and increasing oil production from two to five million barrels of crude oil per day. Between August 1985 and August 1986, crude oil prices plummeted from $28 per barrel to $8 per barrel before stabilizing at $18 per barrel.

During the oil price decline, copper prices also recorded low prices brought about a decline in demand for the metal. The world recession in 1982 – 1984 also pulled down copper prices further dampening demand, which fell more steeply than crude oil.

In the 1980s, the Philippine mining sector started its decline with the closure of several mining companies due to the financial crisis and the occurrence of several mining accidents. Inflation brought about by the debt moratorium crisis in 1983 and unstable political environment, devalued the Philippine peso effecting an increase in the costs of mining production, materials and equipment. Aggravating the situation were the economic crisis and political unrest in the Philippines in the mid-eighties. There were basically limited employment opportunities for new geology graduates at that time.

As a twenty-year-old and fresh from the university, I was practically forced to accept any technical job offered to me. My family was concerned that I would just be bumming around the house after graduation, so I accepted a job as a contractual cartographer at the Bureau of Energy Development (BED) under the then Ministry of Energy. Friends and classmates chided me as overqualified for the job and described my work as nothing but a glorified draftsman.

Beggars can’t be choosers because there were no permanent positions for new geology graduates who have not even hurdled the board examinations. Thankfully, BED management gave us, the new graduates, leeway to review for the board exams. The senior geologists also provided us with a collection of review materials and past examinations for our guidance. However, human resources cautioned us that we would lose our jobs if we fail the board exams. So, we used our allocated time in the afternoon to study and attended review classes in the evening.

In August of that year, a few months after graduating and getting employed in April, I took the board exams. After passing the licensure exams and becoming a registered geologist, I was regularized and became a permanent government employee with the title junior science research specialist.

Fortunately, when I entered the BED, there was an existing World Bank-funded project called “Petroleum Exploration Promotion Project”. The Project aimed to rekindle the interest of petroleum companies in exploring for oil and gas in the Philippines by undertaking a nationwide evaluation of the petroleum potential of the country’s fifteen (15) onshore and offshore sedimentary basins. Aeromagnetic and offshore seismic surveys were undertaken and the information generated was integrated with comprehensive regional basin evaluation studies. The more prospective Northwest Palawan and Reed (Recto) Bank areas in the West Philippine Sea were subsequently included in the study. Complementing the Project was a grant from Petro-Canada International Assistance Corporation, which acquired additional seismic data in selected offshore areas.

The Project also aimed to strengthen the exploration knowhow and technical capabilities of the government implementing entities - the BED and the Philippine National Oil Company Exploration Corporation (PNOC-EC). It was an effective mechanism of training the Filipino technical staff involved in the Project and I was a beneficiary of the knowledge transfer. My colleagues and I were mostly young geologists and geophysicists with very little exploration experience when we joined the BED.

It was in the Project where I initially learned the ropes of petroleum exploration. I was exposed to several aspects of exploration from seismic data acquisition, processing, and interpretation when I was assigned to the geophysics section. It was an effective on the job training for me as I was under the supervision of World Bank foreign consultants and Filipino senior geoscience professionals seconded to the BED from PNOC-EC.

During the marine seismic survey conducted by Petro-Canada, I was sent aboard the research vessel to familiarize myself with the seismic data acquisition process. Marine data acquisition was conducted by using seismic vessels outfitted with sources and streamers that are towed behind the ship. I was seasick for the first few days and was advised to stay in the cabin. When I recovered from motion sickness, my job was to assist in the lay-out and design of the survey lines. I also helped in the quality control of the initial data generated.

It was a spectacular feeling of being out in the open sea. The rhythm of the waves and the wind can help clear the mind and make one feel more connected with nature. I also experienced the sight of so many marine life like dolphins, sharks, flying fish, box jellyfish, and sea birds.

The raw seismic data were then sent to the data processing center. The recorded seismic signals were analyzed to filter unwarranted noise to create an image of the subsurface and enable geological interpretation and identify structures for petroleum accumulation. Under the Project, PNOC-EC set up their own seismic processing center funded by their own loan from the World Bank. Part of my training as a geophysicist was my assignment to PNOC-EC’s Data Processing Center to understand how seismic data are prepared for analysis and interpretation. Seismic data were stored in magnetic tapes and once processed were printed on paper sections.

Seismic interpretation was the last stage in seismic exploration and used to infer the geology at certain depths from the ocean bottom. In the 1980s, data were first reproduced from sepia films using ammonia-based blue printing machines. Seismic interpretation was still done manually on paper sections of two-dimension data using colored pencils. At that time, we pressed our face sideways against the paper seismic sections spread across a long table. By looking sideways, we were able to trace subsurface horizons and large structural traps that could hold oil and gas deposits. We also encoded data and made structural contour maps manually without the aid of modern computer workstations and basin modeling software. The structural maps generated are then incorporated with other geoscience data to create drilling prospects. The exploration geologist would then have to convince higher management that the mapped prospects contained petroleum in commercial quantities.

In addition to mentoring us in the basics in seismic exploration, BED management also allowed us to attend short in-house advanced training courses organized by the World Bank. Foreign experts were engaged and flown to the Philippines to conduct these one-week training courses. The classroom seminars and workshops allowed us to fully understand the theoretical and analytical concepts behind petroleum exploration.

With the change of government after February 1986, and the marked improvement and stabilization of oil prices towards the end of the year, things began to pick up for the upstream petroleum industry. The results of the assessment of the petroleum prospects were assembled in the form of a promotional package contained in 70 sets of a 12-volume report which consisted of a project summary, six volumes of texts and appendices, four atlas volumes and one supplement. The promotion of the Project was finally implemented in 1987 with roadshows conducted by senior government energy officials in major cities in the world to entice foreign oil companies to explore in the Philippines.

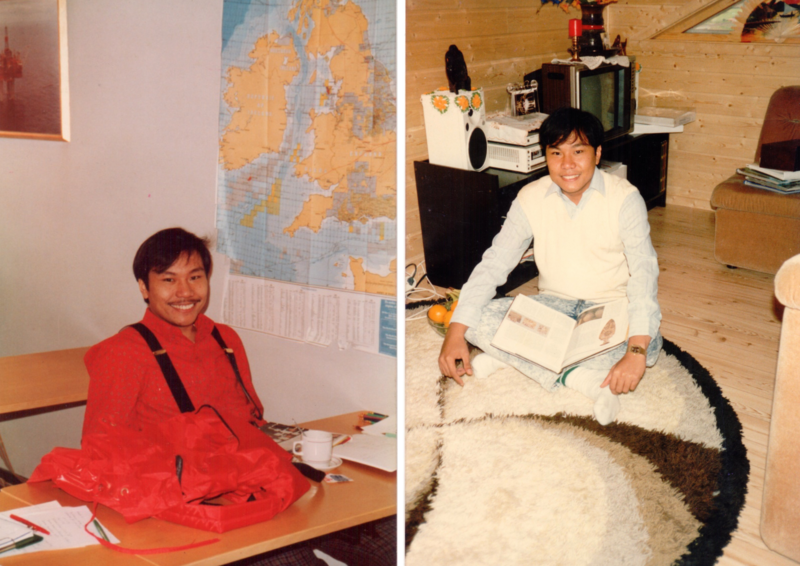

Following the conclusion of the World Bank project, management decided to send me abroad to attend a graduate diploma course on petroleum exploration and production. I was sent to Europe for further technical studies at the Norwegian Institute of Technology located in the university city of Trondheim, north of Oslo. Norway is a major petroleum producing and exporting country tapping the vast marine wealth of the North Sea, one of the busiest but treacherous bodies of water. It has an international assistance program for developing countries like the Philippines, which funded the studies and training of young professionals in different technical fields.

Norway also boasts to have the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, a government-run investment fund that invests in assets such as stocks, real estate, and bonds. The aim of the fund is to ensure a long-term management of revenue from its oil and gas resources, so that this wealth benefits both current and future generations. Investments are spread across most markets, countries, industries, and currencies to achieve a broad exposure to global growth and value creation and ensure good risk diversification.

Selected geologists from around the world were provided scholarships to study specialized subjects in petroleum exploration and production by the Norwegian aid agency. For ten months I was back at the university, imbibing highly technical subjects together with other international students. I studied with inquisitive mainland Chinese whose country was then starting to liberalize their economy and super competitive Indians who have to pass a battery of government examinations to win the scholarship. There were also other Asians, Africans, South Americans, and Europeans with different levels of experience.

A small Filipino community existed in Trondheim composed of nurses and their families, and Filipinas who were married to Norwegians. They took good care of Pinoy scholars, and certainly made life bearable in a far and cold country. At that time, the world was not that globalized yet and Norwegians in a small town have very limited encounters with Asians. Except for a few Vietnamese “boat people” refugees who sought political asylum in Norway from their communist government, Norwegians have but a few interactions with young, dark-haired East Asians like me. On several occasions inside the public bus and train, I noticed blonde, blue-eyed descendants of Norsemen staring and smiling at me. Perhaps my “exotic” looks back then were the precursor of the present K-pop phenomena. If you dare to ask me whether I have had a Scandinavian girlfriend, that is best left narrated in another article.

When I returned to the Philippines after my scholarship, it was the time when the Philippines began to reap the fruits of the success of the World Bank Project. During the late eighties to early nineties, the country was on the radar of large petroleum exploration companies like Exxon, Shell, British Petroleum, Chevron, Atlantic Richfield, Occidental, and other majors. The release of the Report coincided with the discovery of the Camago-Malampaya natural gas field by Occidental and Shell, and the start of oil production from the West Linapacan by Alcorn Petroleum.

It was a bullish era for the upstream petroleum industry. The BED now renamed as the Office of Energy Affairs, following the reorganization and downgrade of the Ministry of Energy by President Corazon Aquino, was busy managing petroleum service contracts and applications. It was then the opportune time to harness my newly acquired technical knowledge. But the irony in government service is that the moment one begins to climb the career ladder, more administrative work is assigned to the individual. In my case, I was charged with more compliance review work addressing the technical and financial qualifications of applicants for production sharing agreements and service contracts.

They say that if you want to see the world, then be a geologist. While there are certainly numerous opportunities for graduate studies and employment abroad for geologists, the profession also has inherent occupational and personal security risks. Field geologists often work in remote, harsh, and unpredictable environments, where they may encounter natural hazards, wildlife, accidents, or even violence. They explore frontier areas rampant in banditry, insurgency, and lawlessness.

My best friend in college who entered the BED with me at the same time, met a tragic accident off the waters of Tablas Island in Romblon province during fieldwork. He was a good swimmer, but he lost his young life trying to save another friend and colleague from drowning when their speedboat capsized in choppy waters. Both died in the accident, and it was such a terrible reminder to the office not to take safety precautions lightly. It was truly heart breaking on my part to inform his parents about his death. A sad day indeed when I was also tasked by the office to retrieve his remains from Romblon and bring him home through a chartered eight-seater plane arranged by the government.

Another blockmate from UP who has a PhD also perished in a helicopter crash together with a nationally renowned volcanologist while doing aerial survey work in the Sierra Madre for the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. Geology is indeed a fascinating and rewarding field of study, but it also comes with many risks and challenges. Geologists also face pressures, such as long hours, deadlines, and numerous travel which take them away from their family and friends.

Why did I pursue a career in law?

(To be continued)

Fernando “Ronnie” S. Penarroyo specializes in Energy and Resources Law, Project Finance and Business Development. He is also currently the Chair of the Professional Regulatory Board og Geology, the government agency mandated under law to regulate and develop the geology profession. Atty. Penarroyo was recently awarded the 2024 Distinguished Alumnus Award for Geosciences by the UP Alumni Association. For any matters or inquiries in relation to the Philippine resources industry and suggested topics for commentaries, he may be contacted at fspenarroyo@penpalaw.com. Atty. Penarroyo’s commentaries are also archived at his professional blogsite at www.penarroyo.com

Reference:

The World Bank, Report No. 8891 “Project Completion Report: Philippines Petroleum Exploration Promotion Project (Loan 2201-PHL)”, 29 June 1990, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/422601468333040235/pdf/multi-page.pdf